Cram Properly

Science and Methods of Memory

The science behind cramming takes a look at how memory works. I’ve talked long and hard about this topic before, but I never really made this explanation easy. I still will probably fail, but not as hard, as explaining how we learn.

Memory

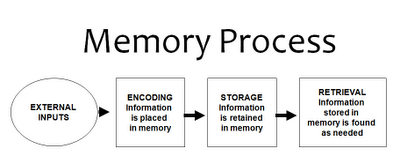

You can break down the process of sensory input and memory in this linear fashion: sensory input -> sensory memory -> short-term memory -> long-term memory. The image below describes in verbs what’s going on. The last box, retrieval, talks about how we bring back up a memory.

Memory Process, Taken from this website

With encoding, we’re looking at the things that we’ve decided to turn into a memory. This has a high importance because this will determine if we retain information or not. If we don’t encode it correctly, we will screw our efforts in learning something. This encoding method is constrained by working memory, which is 7 +/- 2 chunks. This means in our attention span, we’re only going to be juggling only this many chunks at a time. We can think of our attention span as RAM. Chunks here does not mean 7 characters and can take many forms that we can manipulate. For example, one chunk can be a phone number, it can be a word or a phrase, it can be a pneumonic.

With working memory as our constraint, we consider this a drawback from learning faster. This means we’re not going to process more information without properly going through the rest of the memory process beforehand. However, methodology is important here about how to space each session of this working memory. For example, each chunk of information can be mixed and combined with each other using association and serial position effects. Association with existing knowledge in your long term memory could save you time in remembering something, which is important when learning concepts and ideas, especially something that begins abstract. For example, remembering someone’s name is difficult because you haven’t placed it further that your sensory memory. A name is difficult to recall after the first meeting because it’s an abstract construct in our mind. If you try to associate it with another friend who has the same name, it will be easier since that name is already encoded in your mind. You don’t have to necessarily associate it with another person either; it can be an inanimate object or a koan. Serial position effects will allow you to group things in the order you received the information. For example, you’ll have a better time remember the items of a list in the first and last positions than the middle. If the list items are closely related to each other in the beginning and the end, you’ll have an easier time associating these words and merging chunks together. There’s other effects you can try to pull with lists as well, like the Von Restorff Effect in which you place a unique signifier in the middle of the list, like a curse word or something that doesn’t sound right.

There’s a time constraint with encoding, which is about a minute, before you forget this information. That’s why proper spacing in terms of attention span and new information is critical. The best methods out there for this is the Anki method, which uses this data of how often we’ll forget something and make you recall it afterwards. This is best for things you can put on flash cards because you can recall them anytime after using a timer. Many applications are built around this method. My personal favorite is Memrise on Android that really helps with language learning vocabulary. Other ways of approaching the time constraint is utilizing breaks, which is why coding marathons are not as effective as someone taking breaks in between coding sessions because of fatigue and attention span. What really utilizes this well is the Pomodoro Technique, which introduces breaks in your sessions of work properly.

Not everything is a flash card though. Sometimes the abstract needs remembering, and flip side answers in flash cards just won’t do. This is when you take different approaches, like R-mode first followed by a switch to L-mode activity. I mention R-mode here, but this does not mean right brain. If you split the brain in two different processes, there’s L-mode and R-mode and has been given other names by other scientists in different fields. For example, Daniel Kahneman thinks these as system 1 and system 2. I won’t go in heavy discussion about this because there’s a letter I wrote over a year ago explaining this in full detail. Now that we have that down, this activity that you do pairing each process with an activity is important. One activity is something I’m currently doing with you, which is recalling all of this information and trying to teach it to you. Other ways include doing the operations if your learning something that involves motor skills (e.g. just climbing before you get climbing lessons from an instructor), using metaphors to describe what you learned (really neat way of pairing two things that don’t seem to mesh well, pair programming, and a general exposure to a foreign language spoken to you in a dark room (see Lozanov Seance).

The conditions in which we learn is also critical. Your well-being can influence the efficiency on how you learn. This is heavily tied with the amount of rest you receive each night (duration and the number of REM cycles are really important here) and physical and emotional fatigue.

Then we arrive at storage. Our brain is not an efficient storage system, so we’ll issue lags in memory for certain things we think are easy to recall, like birthdates, names, that title of the song you heard earlier. Your R-mode side of your brain will run this tasks with your unconscious riffling through each thing until it finds what it’s looking for. This is the effect experienced when your in the shower and you finally figured out the name of that song you heard.

One way memory athletes have approached this issue is by the Method of Loci, also known as memory palaces. This is where you take a familiar room or space in your mind and fill it with things to remember by using unique signifying objects. This technique is really powerful and can help you remember a deck of cards (which is correlated with counting cards in a casino) and in general skill acquisition operations. You have to go back a step and re-encode your memories, but having this visual memory palace could remain as one chunk and you’ll be able to recall things a lot easier in a class (using the programming analogy here).

Lastly is retrieval. I’ve talked extensively about skill acquisition, heuristics, and snap judgments before. As aforementioned, there are two ways of approaching retrieval, which is the slow process and fast process. The fast process are heuristics, or snap judgments. The slow process takes longer and you start to stretch your mind looking for more credible answers. Fast processes are stimulated by the external inputs, which can lead to some nasty outcomes (Read: Blink by Malcolm Gladwell). What’s important here is that if you slow down that reactive side of thinking, you’ll be able to think more clearly about certain decision points in the learning curve a lot better. And yes, go back to the letter about learning curves if you want to hear me talk more about that as well.

So to the question at the beginning, how much can you cram in one day? This depends on your method of cramming. For myself, I’m working on taking breaks and using other methods to properly encode it in my brain.

Written by Jeremy Wong and published on .